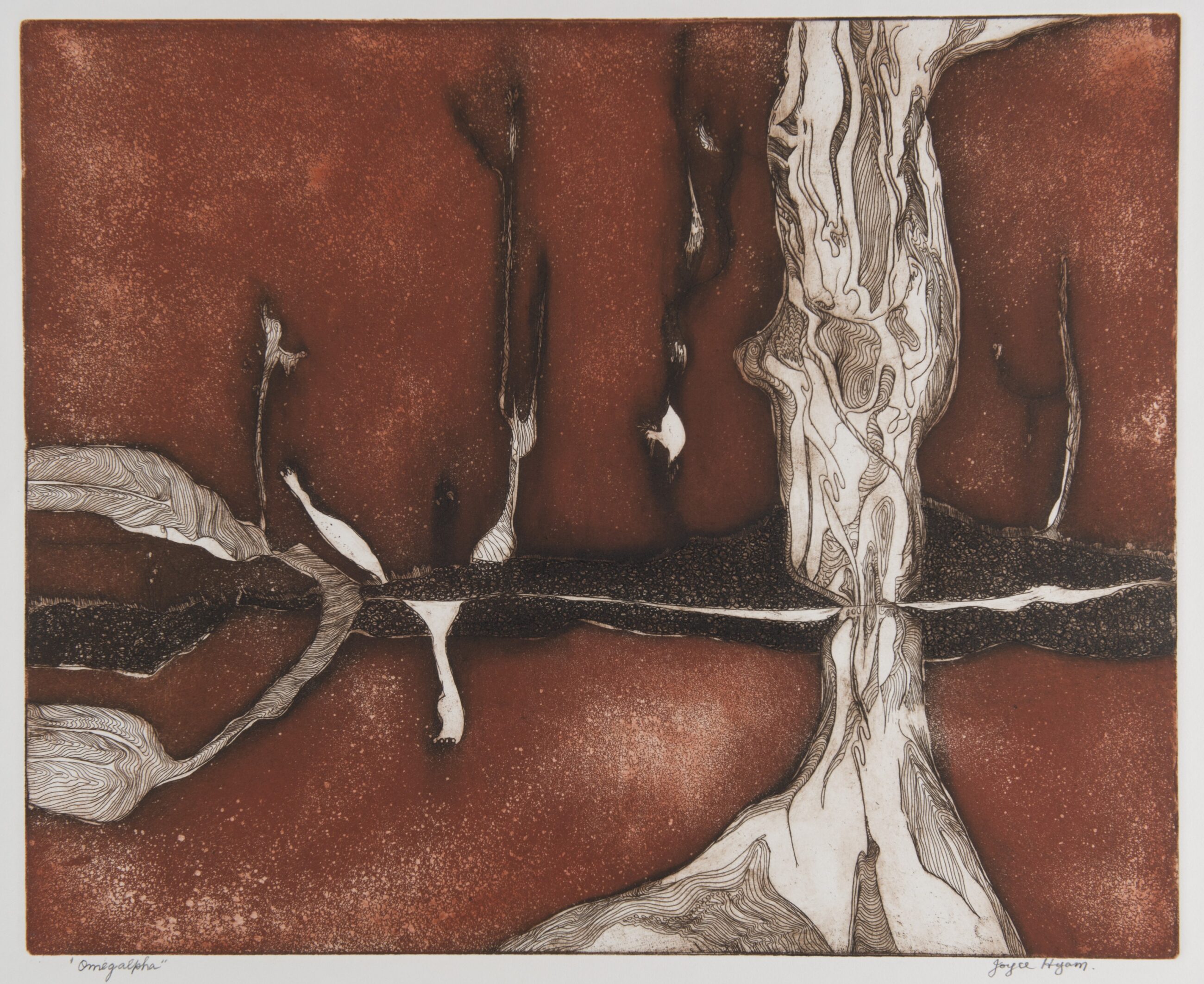

“They don’t know what sort of artist I am, because I keep changing” – Joyce Hyam

Joyce Hyam was a prolific artist whose practice encompassed painting, printmaking and textiles. Born in Brisbane in 1923, Hyam studied at Brisbane’s Central Technical College and Queensland College of Art; also undertaking private tuition in Brisbane and during a brief period in Munich. Her own teaching career, spanning 1963 to 1994, was as diverse as her artistic practice. Hyam died in 2021, leaving behind a strong legacy as a significant 20th century Brisbane artist.

Cribb Island: Brisbane’s Lost Suburb showcases a captivating series of Hyam’s watercolours depicting the now erased and largely forgotten suburb in Brisbane’s north. Weathered homes, abandoned boats, mangroves and mudflats – the inky images tell the story of a suburb past its glory days, yet rich in character and with undeniable artistic appeal.

Hyam had been a frequent visitor to Cribb Island since her childhood in the 1920s, with her aunt owning a beach house in what was then a bustling seaside destination. The artist’s Cribb Island scenes were produced later in the 1960s when, accompanied by fellow artist Dr Irene Amos OAM, she went on painting trips to the suburb, before it was resumed by Brisbane Airport.

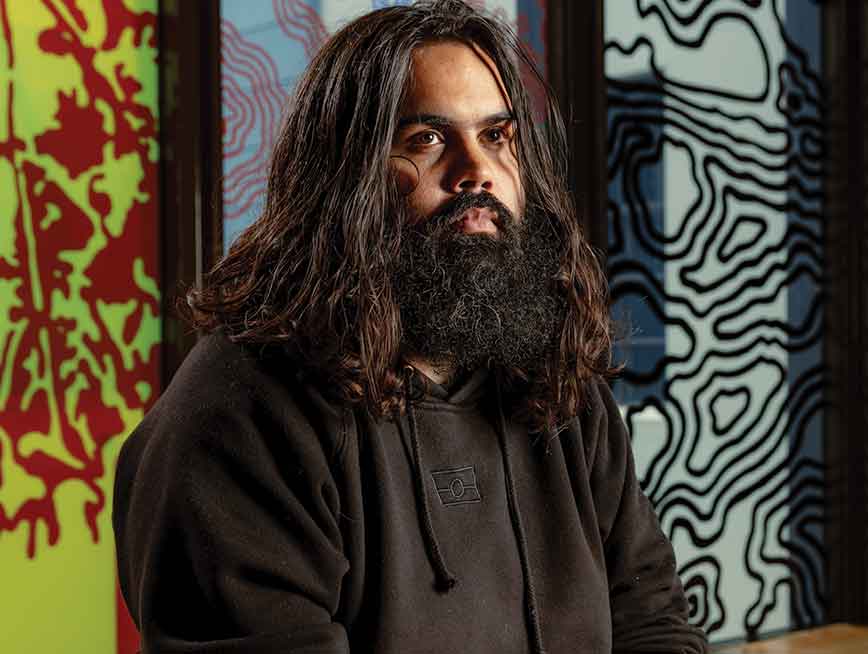

Joining Hyam on many of her painting trips was her daughter, Vivien Harris. We had the privilege of speaking with Vivien about her mother’s work, the importance of documenting women’s art, lifelong curiosity and the gift (and challenge) of not fitting into one box.

Vivien, you’ve been a strong advocate of Joyce’s work for many years. You’ve not only ensured that her art is represented in numerous collections, but you’ve also published two books. Can you tell us about this journey of deep engagement with your mother’s life and work?

Well, it’s a privilege, really, because I’ve got time in life now. The impetus of this journey started in 2014, when I published the first book, in collaboration with her big retrospective at the Royal Queensland Art Society. That exhibition, for me, was the culmination of my mother’s life as an artist. The exhibition was attempting to represent her journey from when she first started painting and drawing, right through the printmaking, through to the textile era. And that’s where I thought if the artworks that we own, particularly the ones that I inherited from my mother, could go into various galleries and museums, they’d be better placed there. They’ll be displayed from time to time, they’ll be looked after and they’ll also represent an era of women’s art in Brisbane that is so important to have documented. And so, I started approaching various museums and organisations, and every one of them has willingly and enthusiastically said, “Yes, we’d love those works”.

Joyce’s career spanned not only decades but also an extraordinary range of artistic mediums. Could you walk us through the evolution of her practice?

I was very interested in her progression. When I was a child, she was mainly doing watercolours and acrylics and oils in more traditional styles – although watercolours enabled her to become more fluid and spontaneous and more expressive. When she first started, her works were very representational. She’s formally trained in art, so she was conscious of the elements of art – of colour, line, shape, form, texture and composition. As she became more confident and more practised as an artist, she freed herself up and became more creative, moving into more abstract kinds of representation. She was also a person who liked change. She didn’t want to do the same thing all the time. She could have stuck with watercolours and done watercolours all her life, or she could have stuck with drawing and done drawing all her life – or printmaking. But she’d explore one medium, and not necessarily master it, but feel comfortable that she enjoyed exploring that medium, and then she thought, oh, I can do something else now – I can go on and use acrylics and see what acrylics will do, that watercolour doesn’t. Each medium has its own potential and its own capacity to be expressive. After she finished acrylics, she thought, oh, I’ll try printmaking. It was a bit of a surprise because I never knew what she was going to do next.

I’d moved to Canberra, and so there was a period of about a decade where I didn’t really see a lot of what my mother was producing. During that decade she started doing printmaking and she was going to various classes, learning viscosity etching and lithography. She really did some beautiful work during that time and got some rave reviews from art critics. But she stopped doing printmaking for two reasons: firstly, the inks you use in printmaking are quite toxic, and secondly, it was heavy work – she found the plates to be too heavy. When she started textile work, I thought, oh, she’s not painting anymore! Now she’s doing something new! She’d go up to the University of Southern Queensland in Toowoomba and she would do a whole winter or summer school on one particular textile technique. It might be creative stitchery, freeform machine stitchery, or it might be appliqué, or dyeing fabrics, or making art garments. Drawing was the most important element that goes right through her art. Even in her textile art, she would draw some figures or draw a picture and then paint that picture onto the fabric or stitch it with free-form stitchery. So drawing was really a significant thread right through her career. You see it in her lithographs and her viscosity etchings, and you see it in her printmaking.

She had her own art studio at the back of the house, set up from when I was a child, for everything she needed. And I watched all those transitions. She used to use the word ‘play’ a lot when she was in that art frame of mind – which she was a lot. Dad would say, “What are you doing now, Joycie?” and she’d say, “I’m just playing, Frankie”. So, it was a joy for her; she was always happy. But she couldn’t put herself into an art frame of mind because someone wanted her to. So, as much as I use the word play, it was purposeful and it was her own decision to immerse herself in the art when she felt like doing it.

With such a broad practice, where did Joyce sit in the art world? And what role did the art community – particularly her female contemporaries – play in her development?

I think one of the disadvantages that Joyce always had was, as she put it, “They don’t know what sort of artist I am, because I keep changing”. When you see her artworks up on the wall, people say, “Is that the same artist that did this?” Because they’re so different! That was an advantage, but also a disadvantage, because the art world couldn’t put her in a box – “That’s a Joyce Hyam”. They couldn’t identify Joyce Hyam, because Joyce Hyam kept changing! So, her versatility was exciting and wonderful, but it also meant that there wasn’t a kind of capacity for the art world to actually identify her as an artist. She’s much more well known since the books and since she’s had exhibitions and so forth, so that’s not a worry anymore. I don’t think she even worried about it anyway. She didn’t care – she just did her art. And she gravitated towards people who were like-minded. The Contemporary Arts Society [1] – the women who were in that group – they all painted together and enjoyed exhibiting together. They were all very different as artists and they didn’t judge each other’s art. They all valued each other’s artworks! And then in the Wednesday Group [2] – it was the same – and then in the Textile Ten [3] . All of the artists in the Textile Ten produced such vastly different works and that’s really enriching. It’s lovely to see the diversity of those women artists that she associated with. And of the men – she learnt from some quite famous men, like Jon Molvig and Stan Rapotec and John Aland. She taught with and exhibited with William Robinson and Margaret Olley, and I think they influenced her too. She did learn a lot about art making from some pretty well-known artists, and that added to her capacity, as an artist, to be who she was.

Joyce credited her mother, Gladys, as a formative influence. Gladys was an artist in her own right who, like so many women of her generation, didn’t have the opportunity to pursue art professionally. So, Joyce was something of a pioneer in that sense, not just in her family but also as a part of a growing community of women artists in Brisbane…

You’ve expressed that well. Her mother did influence her artistry and I think there must be a genetic element as well. Gladys was the youngest in the Keene family, and she and three of her siblings went to England with their family, where she was going to study art. The First World War broke out while they were there, so they ended up only staying a few months before coming back to Australia. My grandmother then briefly did a course with Vida Lahey – and her artwork is exceptional; she was gifted as an 18-year-old. My grandmother ended up having to pursue a career in nursing. She couldn’t have supported her family in art, so that was the end of her art career. But I think that influenced Joyce enough to be inspired by her mother’s artwork and to, as you say, carry on that legacy that was never actually realised, because women’s work was at home, rearing children.

Joyce was very much amongst women artists. I guess that collective of being – of painting and drawing and exhibiting with other women artists – was in itself very feeding. They were promoting themselves, promoting their artworks, promoting the fact that women can be artists and they can produce wonderful works. So, she didn’t let that stop her. At the time, it was certainly men who were achieving accolade in art, but women weren’t – even though they deserved it. Nowadays that’s changed. Galleries and museums and the art world are now equally, I think, representing women as much as men. I hope they are.

Footnotes

[1] Hyam was a founding member of the Contemporary Art Society in Queensland. She exhibited her sculptural work Cracked Bowl in their first exhibition at Hardy Brothers Gallery on Queen Street in March 1962.

[2] The Wednesday Group mostly comprised female students of Roy Churcher, a prominent abstract artist. From 1961, members including Mary Norrie and Dr Irene Amos OAM would meet in the studio at St Mary’s Anglican Church, Kangaroo Point, every Wednesday.

[3] Hyam joined the Textile Ten in 1993. The group met regularly to discuss their contemporary textile works and frequently exhibited across the Brisbane region.

Come and see Joyce Hyam’s inky watercolours of Cribb Island up close. Cribb Island: Brisbane’s Lost Suburb is showing at Museum of Brisbane until 26 July 2026.