Joachim Froese’s practice spans analogue and digital photography. Embracing a wide range of technologies and techniques, from salt prints to smartphones, his work investigates the role of photography in shaping our perceptions and understandings of the world.

We caught up with Joachim to learn more about his photographic practice and his artwork Dorothy’s Birthday 2.0, which is currently featured in New Light: Photograph Now + Then.

Your practice spans both analogue and digital photography. Can you tell us more about your practice and the ways in which you work with both traditional and contemporary photographic techniques?

When we talk about photography, we often forget that the term encompasses a wide range of different technologies and processes—each offering its own practical and conceptual possibilities. My current practice combines historic printing techniques with contemporary digital capture. It’s a way of exploring photography’s past while engaging fully with the present. To begin with I take images with a digital camera, sometimes a mobile phone, or download images from the internet. Then I rework these digital files in Photoshop. But instead of producing standard digital prints, I render them as salt prints—the earliest photographic printing process on paper, introduced by Henry Fox Talbot in 1839.

Salt printing is slow and entirely manual: the paper is hand-coated, exposed under UV light, and toned and washed by hand. This contrasts with the speed and ease of digital capture, and the hand-made nature of the prints disguises their digital origin and manipulation. By fusing past and present, I invite reflection on photography’s materiality and history: photography’s shifting forms, and the enduring human desire to record, remember, and understand our place in time.

What does photography as a medium allow you to explore that other art forms might not?

I’ve been taking photographs since childhood—long before I ever thought of becoming an artist. Friends from those days often say they rarely saw me without a camera. Back then, not everyone was a photographer. Today, in the age of mobile phones, we all take photos constantly, and for many, social media has become a kind of virtual extension of themselves. No other medium is used so pervasively.

This ubiquity is precisely what sets photography apart. It operates on so many levels at once. Beyond the everyday consumption of photogaphy, the medium is embedded into art, technology, and science. It blurs the boundaries between private and public experience. For me as an artist these crossovers offer endless inspiration for both creative and conceptual exploration.

But my fascination with photography goes beyond artistic practice. I’m also an academic, focused on the medium’s history and theory. For me, taking photos and experimenting with new techniques is just as vital—and enjoyable—as studying and teaching how photography has been used and understood, both historically and today. Making, thinking, and teaching photography have become deeply intertwined. Understanding the medium in all its complexity has become a lifelong pursuit.

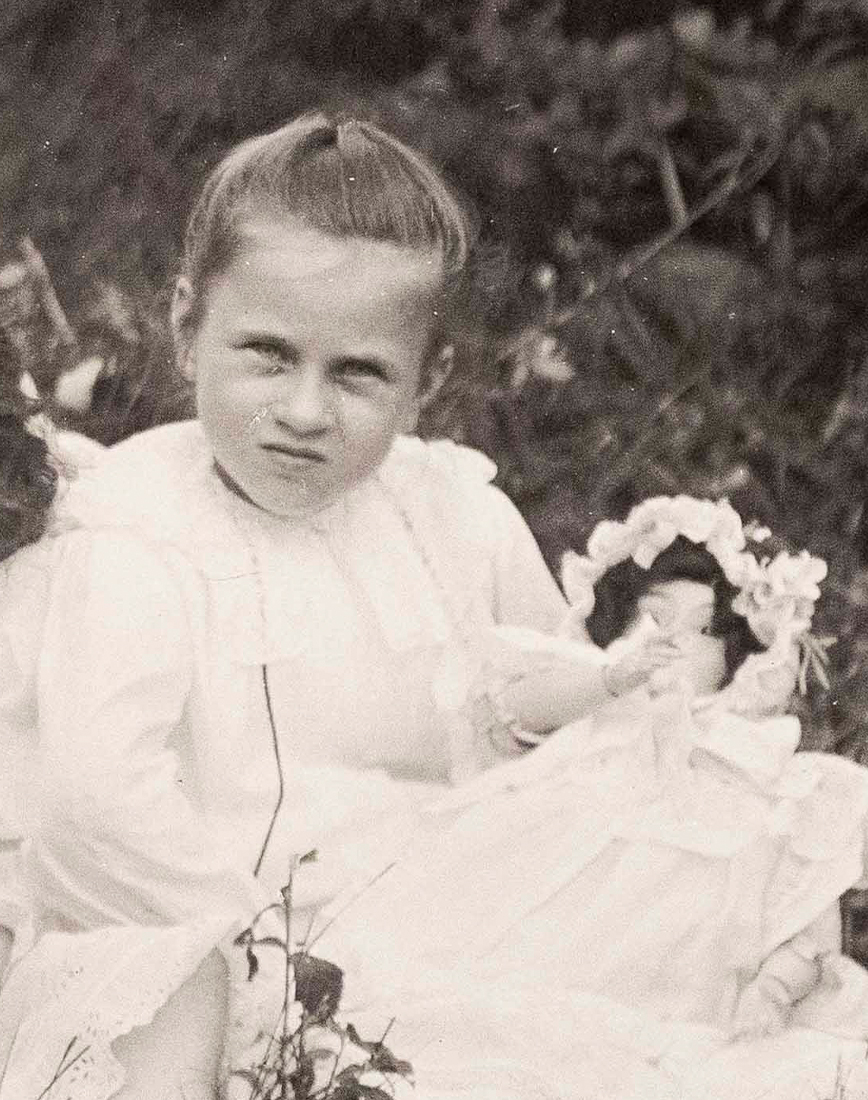

What initially drew you to Alfred Elliott’s photograph of his daughter Dorothy’s birthday party in 1911?

When Elena Dias-Jayasinha, the curator of New Light: Photograph Now + Then, invited me as one of the artists to respond to the Elliott Collection, she showed me a wide range of prints, mainly depicting the changing face of Brisbane in the first half of last century. But mixed in with all these images were some of the personal photographs Elliott took, and the one of Dorothy’s birthday party really stood out to me. I guess the reason why it caught my eye was the way the people in the image were staring right at you. I suppose at first, I just stared back at them.

But it was when Elena told me more about the background of this scene that I really got hooked. You can speculate a lot of family relationships in the image: a sulking Dorothy is sitting at the edge of the group, looking pretty miserable, while her brother Alfred, looking pretty smug is hogging the limelight, even on his sister’s birthday. I’ve always been fascinated by vernacular family photos and how much they tell us far beyond the intentions of the photographer.

Your work, Dorothy’s Birthday 2.0, restages Elliott’s photograph of his daughter Dorothy’s birthday party using smartphones and a tablet. What interested you in revisiting this moment, and what ideas or questions did you hope to explore by reimagining it through a contemporary lens?

I was drawn to Elliott’s photograph not only because it provides us a glimpse of social lives from a bygone era. I wanted to revisit this domestic moment because I asked myself what it might look like today—not just visually, but structurally. I was interested in how historic and contemporary technologies both shape the act of photography and the way we relate to one another, and I began to reimagine the scene displayed on smartphones screens.

Consequently, I reversed my usual approach. Instead of showing something new in an old way here I show something old in a new way. To create Dorothy’s Birthday 2.0, I used a digital scan of the image and cropped out all the people attending the party. I then restored their faces and manipulated some of the images to transfer them onto smartphone screens. Finally, I arranged the phones displaying the ‘new’ images into a structure that puts Dorothy rightfully into the centre of attention.

The piece is meant to be a tribute and a playful critique—a way of asking how much has changed, and how much hasn’t, in the way we see and structure family life.

What do you hope people will take away or reflect on when they experience your work in New Light: Photography Now + Then?

First and foremost, I hope people pause and spend a little time with the work. I introduced subtle changes that invite for closer observation: changing faces, rearranged positions, swapping out the toys the children hold.

I want people to move back and forth between Elliott’s original image and my new version, to notice what has changed and what has stayed the same. In doing so, they might begin to reflect on the evolution of photography and family representation—how the ways we document ourselves have changed with technology, and yet how the impulse behind it remains surprisingly constant.

It’s also important to me that the work doesn’t feel heavy or didactic. I hope there’s a lightness to it—a subtle humour—that people might pick up on. I want viewers to feel intrigued, maybe even amused, as they piece things together. It’s about encouraging a playful kind of looking, one that allows space for personal interpretation and quiet reflection on both photography’s history and its place in our everyday lives now.

Discover more about New Light: Photography Now + Then