Having grown up on the volcanic shores of Taribelang Bunda, Gooreng Gooreng, Gurang and Bailai Country, Anita Holtsclaw’s works explore our relationship to the poetic coastal landscape.

Residing in the Adelaide Street Pavilion from 16 June–23 October 2022, Anita’s exhibition Estuary will ebb and flow as she explores the presence of water in our lives and bodies. Beginning with three ethereal works, the space continues to evolve as Anita experiments with intricate embroidery techniques to create new works and embellishes the gallery walls with a large-scale drawing.

Embracing the emotive qualities of moving image media and sound, Anita’s artwork is conceived and made where she lives and swims. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at QAGOMA, Brisbane and Citè International des Arts, Paris.

We caught up with Anita to find out more about her residency.

MoB’s Artist in Residence Program is supported by Tim Fairfax AC.

Your exhibition, Estuary, and practice more broadly contemplates the ephemeral nature of water and our connection to it. How did your interest in water begin? Was there a moment or memory that stimulated your curiosity for this subject?

From my very first moments onwards I’ve always been drawn to the water and was very lucky to grow up with the sea in my backyard. As a child I’d spend most of my time exploring the rockpools in front of my home or swimming. On rainy days I’d look out to the sea to watch how the horizon and sky would meet. I was fascinated by the way the water would change every day from calm to rough dependant on the weather. I also loved to watch how the colours of the sea and sky would shift throughout the day. I still love seeing the full moon rise over the sea and feel most at home when I hear the sound of the waves as I go to sleep.

For Estuary, you’re exploring how the Brisbane River flows from the upper catchment to meet the sea as well as the ecosystems that play out along its banks. What research has informed this exploration and how do you hope to represent your findings within your residency?

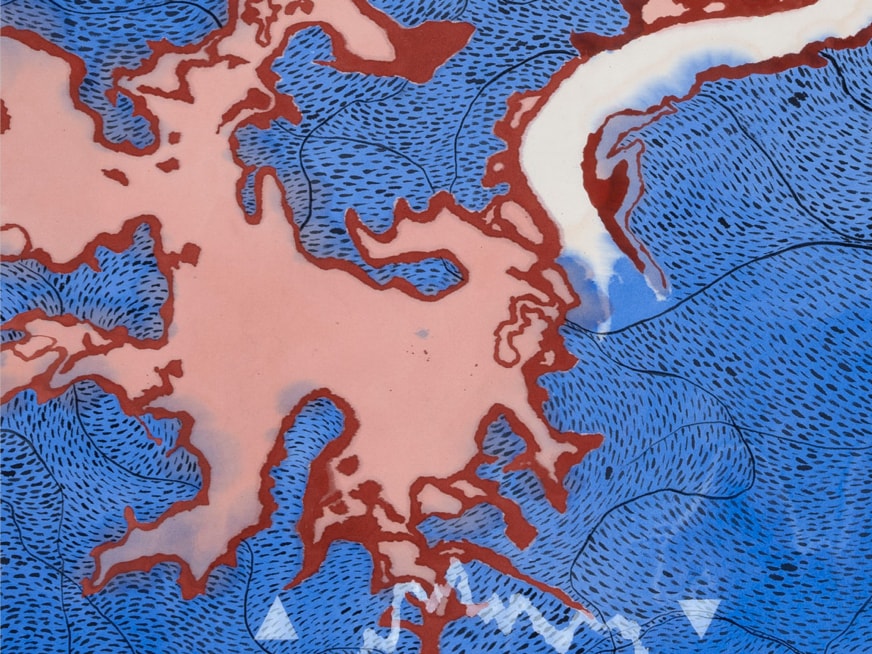

While I was thinking about this project, I was drawn to how the river functions as an estuary. I spent lots of time visiting different areas along the banks of the river to spend time with the water and see what was there. I documented the plants such as the three different kinds of mangroves represented in Estuary as well as how the colour of the river changed during magic hour. From this initial onsite research, I then spent some time finding out more about each of the mangroves as well as reading up on how the riverbed has changed over time from the First Nations use of the river when it was loved and cared for and was beautiful and clear, to the dredging of the river post-colonisation and our mixed use of the river in Brisbane today. During my residency I will be continuing my research, finding out more about the unique ecosystems of this waterway and representing the many flows of the water through the line drawings on the gallery walls. These line drawings trace the many ways the water moves along the riverbank from times of drought to flood and all the spaces between.

As part of this exhibition, you have created three large-scale embroidered works, as well as a live wall drawing which is unfolding in the space. What draws you to the decorative arts and what does your process look like?

In my practice I make all kinds of artwork from installations to 16mm moving image film works, ceramics, fabric embroideries and drawings. I’m drawn to the decorative arts as they were historically an artform associated with women that was seen as lesser than the ‘high art’ produced by men. Most of the decorative works made by women were produced for the home and I’m interested In the loving care that goes into creating warm and meaningful interior spaces. My process is two-fold and involves both research and play. I normally begin a project with an idea, in this case the starting point was how the river functions as an estuary, a vital living space for plants and animals. From there I thought about the residency space. The Brisbane City Hall site is an area of great cultural significance for First Nations people and was once a thriving waterhole. The building has a rich decorative history from the carvings and furniture to the hand painted walls and soft furnishings. I then thought about how I could represent this in the space and decided to create wall drawings that reference the water that flowed on this place as well as the decorative history of wallpapers the adorned the walls of buildings of this age. The embroideries that hang from large, oversized hoops reference the unique visual features of the three different kinds of mangroves in abstract stylised form. I created them by first sketching up some ideas before laying out freshwater pearls, silk and thread on voile. I play with the arrangement of the materials and often make small toiles before completing the larger pieces.

You mentioned your focus on using recycled materials to create artworks. How do you source your materials? Are there stories tied to the materials you are using?

For my work I think about what each project needs, how the materials directly relate to what I’m creating as well as my ecological footprint as an artist and find that materials often present themselves to me. For instance, in Estuary, I’m using a recycled voile that has lived a few lives already in some of my previous large-scale installation works such as Searching at Metro Arts where I sculpted the fabric into waves and sea foam that spanned the beautiful historic floorboards of the old gallery on Edward Street. In Estuary it has been steamed and stretched across the hoops to form a smooth water-like diaphanous surface. The hoops themselves feature bespoke hardware made by a resourceful metal smith Glen Urquhart. These came about through a conversation I had with Glen after not being able to find any suitable hardware for the hoops that were in production. I stopped by Glen’s workshop that’s handily located at the same site as my own studio to see if he might be able to make something out of brass for me. We were talking for just a few minutes when Glen disappeared into his pile of recycled metals and pulled out some copper. It turns out that this copper was originally used to power the workshop and has lines of its former life running through it. This is the same copper that I used to design the rollers for the collaborative paper drawing.

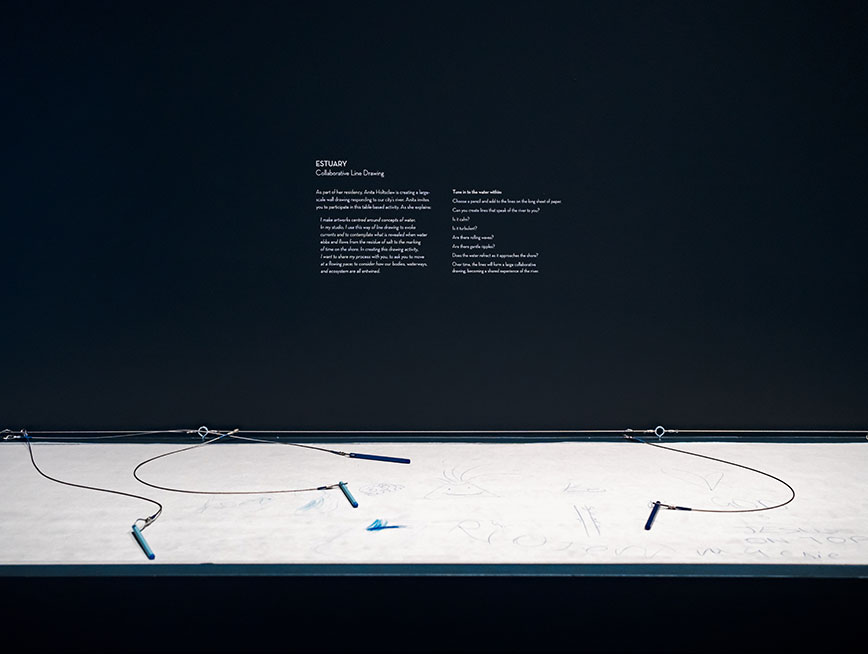

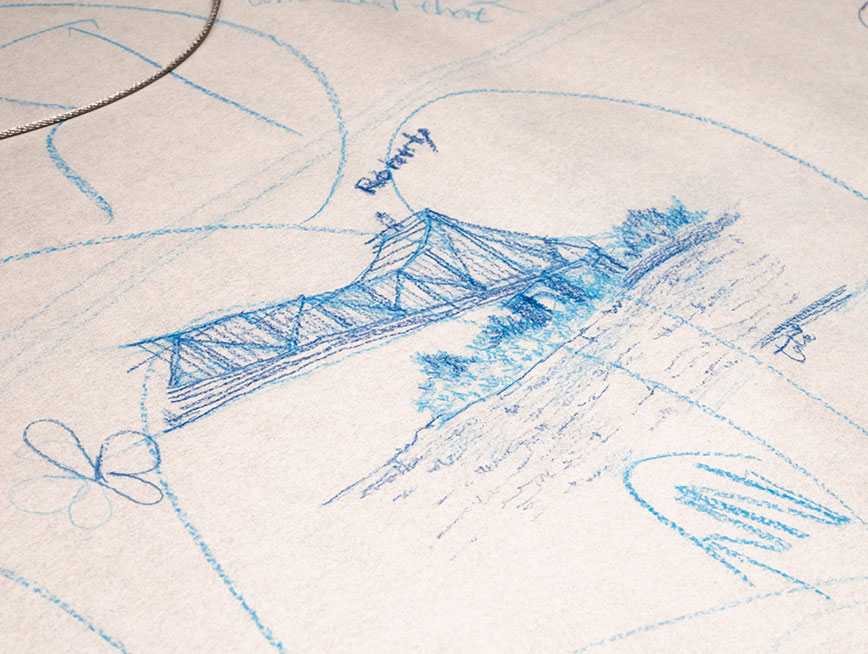

The Museum community can contribute to your project through a shared drawing activity. What do you hope to achieve through community collaboration?

In the collaborative drawing activity I’m hoping to share with the participants my connection with water as well as my process of drawing. My line drawings came out of an initial exercise where I would draw lines with chalk on a large black canvas in my studio as a way of reconnecting with practice. When making this kind of drawing you don’t need to be traditionally skilled or magically gifted in order to make something meaningful and beautiful. Instead in this way of working lines are built up, each person adding to the work of others to create a larger continuous drawing that shifts and changes just as the water in the river does. It’s never the same water, constantly combining with other sources before flowing out to sea.